Imagined, experienced, remembered? A trio of selves digest Stranger Things

I finished Stranger Things a few weeks ago and my first thought was: it’s no Succession. Ending a beloved series that’s been running for almost a decade can’t be easy, proven by the fact very few have done it successfully. In one review I read, the Stranger Things finale was applauded for playing it ‘straight down the middle.’ Not a dumpster fire like Game of Thrones, not a masterpiece like Schitt’s Creek. It was fine.

Did it make me cry? Yes. But did I have a general sense that the plot wouldn’t stand up to scrutiny? Also yes. After five seasons, the synthy neon nostalgia and twee cinematography felt a little too effortful and irksome. The acting aged like milk. From my perspective, Stranger Things peaked in Season 4.

Naturally I’m unable to simply accept this thought and move on, I need to understand why I feel this way.

Endings matter. We know this inherently, but it’s supported by a fascinating piece of behavioural psychology research conducted by Daniel Kahnemen in the nineties known as The Peak-End Rule. His study wasn’t linked to storytelling at first — he worked with patients going through painful medical procedures and established that the way an experience ends affects how a person remembers it.

Kahnemen theorised that each of us has two ‘selves’. First, there is the ‘experiencing self’ which is the one that asks, “does it hurt now?” The experiencing self exists only in the present moment. It’s narrative-less. Only after an experience is complete does the second ‘self’ take over. The ‘remembering self’ is the one that asks the question, “how was it overall?” It looks back on an entire experience and bestows meaning. This self is built upon narrative. Kahnemen said, “the remembering self does not care about duration, it cares about the peak and the end.”

It wasn’t until about a decade ago that this research began to be referenced in storytelling and marketing literature. The key transferable principle is this: the stories we remember best have strong emotional peaks and endings. That’s not to say the other parts of our favourite stories aren’t important, only that if you don’t get the peak and the end right, the rest will simply be forgotten.

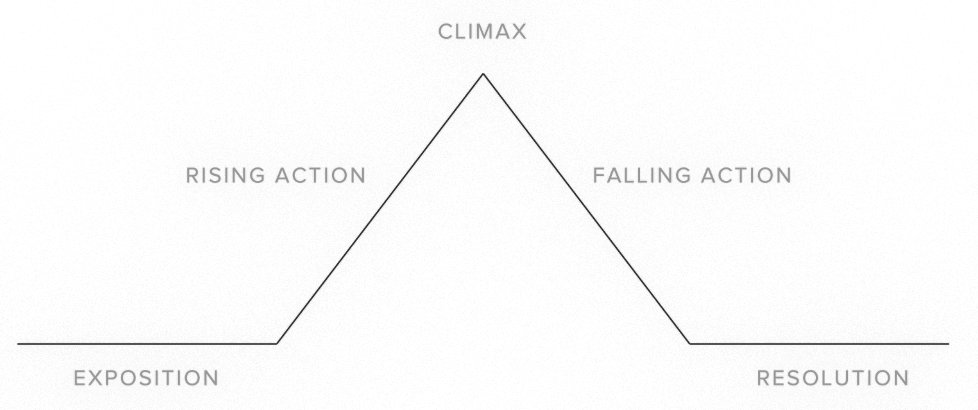

To understand more about peaks and endings in storytelling, it’s helpful to look at a traditional story structure like Freytag’s Pyramid. This was developed by Gustav Freytag in the 19th century through his study of classical and Shakespearean drama.

The pyramid looks like this:

Exposition – the world, characters, norms

Rising Action – complications and pressure

Climax – the point of maximum tension

Falling Action – consequences of the climax

Resolution/Denouement – resolution / new equilibrium

If we pair these two ideas together — Kahneman’s Peak-End Rule and Freytag’s Pyramid — it becomes clear that if you want your story to be remembered, you need to focus on the climax and the denouement.

Stranger Things is a sprawling multi-dimensional epic with a giant cast, so the task of doing that is incredibly complex. It requires creating a clear pyramid for each character, relationship, plot line, episode, and season. Then, somehow, bundling all of that into an emotionally authentic series-level climax, followed by a well-paced falling action and denouement that allows the audience to say goodbye to the world and its characters.

Here’s where Succession had something going for it that Stranger Things never did. The entire series, from S1E1, was always barreling toward one emotional climax: the death of Logan Roy. When they finally killed him in episode 3 of the fourth season, the writers still had seven episodes to allow for the falling action and denouement. The ending began early. If we look at IMdb episode ratings for Succession Season 4, it comes as no surprise that episode 3 (emotional peak) and episode 10 (denouement) are the highest rated.

Stranger Things was written to be a one season wonder but its runaway success resulted in renewal. When the first season was written, the Duffer Brothers had no inkling of what popularity would demand of their characters and storylines. Allegedly, they envisaged future seasons following the style of shows like Fargo and True Detective, with completely new environments and characters each time. But the global audience’s attachment to Mike, Will, Eleven, Joyce and Hopper meant the studio asked them to retrofit the narrative to reach for an unknown end point.

With no clear emotional peak to point towards, Stranger Things careened through its final season. Massive plot points were still being revealed in the penultimate episode (it was a wormhole this whole time???). The sheer size of the cast made it difficult to pick a ‘winner’ to lead the audience to the peak. This is always difficult with ensemble casts, but even in Schitt’s Creek, one of the greatest ensemble casts of this decade, the audience understands that David is the key protagonist around whom everything hinges. It’s not that we don’t care about all the Roses, we just appreciate that their stories are supplementary to the central romance.

In Stranger Things 5, the writers (and the audience) seemed torn between Will and Eleven as drivers of an emotional peak. I would argue that across the series, Will’s arc ended up being the most clear and satisfying, and judging by the fact that ‘Sorcerer’ is the highest rated ST episode ever, it seems the rest of the audience agrees. Eleven’s peak came way too late to be satisfying. There were too many loose ends to tie up, leaving inadequate time for a falling action and a denouement. The show only really began the process of ‘ending’ in the final nostalgia-filled D&D scene, which almost acts as an epilogue.

I still felt sad to say goodbye to those characters, but I look back on the rest of the series and feel as if I’ve already forgotten it.

I have respect for the Duffer Brothers for the narrative world they created, the characters, the intricacy. I have respect for a good enough stab at the impossible task of ending it. I certainly couldn’t do what they did, in fact, I was talking to a friend about this topic a few weeks ago because I realised that due to my inability to finish stories I have virtually no experience when it comes to writing endings. She suggested I start with an ending for once. I’ve been trying and it’s hard. It’s as if there needs to be a third self in Kahnemen’s theory: an ‘imagining self’ – one that visualises how an ending might feel and constructs a narrative to make that ending a reality.

That’s the art of fiction, but also, maybe, of life? I was telling my son about Alex Honnold today, the man who just climbed one of the tallest skyscrapers in the world with no ropes live on Netflix. It was terrifying to witness but Honnold was unfazed. In the 90 minutes it took him to reach the top he was cracking jokes, waving at bystanders through the glass, and listening to Tool. He climbed like a man who already knew the ending. I read an interview with him before the climb, and when he was asked how he prepared he talked about how he likes to imagine the feeling he’ll have while he’s climbing.

After telling my son about the peak-end rule, he asked which of Alex Honnold’s selves would have been climbing the building and I told him it would definitely be the ‘experiencing’ self — but maybe I’m wrong. Maybe the ‘imagining self’ is the persona he steps into when the moment comes because it makes him invincible, eternal, pre-destined to succeed. He certainly created an epic ending at the top of Taipei 101 by saying the simple word, “sick". Lol.

Maybe that’s the self I need to find. The Imagining self of @courtpet, master of peaks and endings.