Give ’em something personal: parasocial connection and the illusion of intimacy

I think my first parasocial relationship was with Lucy Pevensie when I was six. After finishing The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, I opened every cupboard in every building I visited, convinced if I just believed it enough I’d find Narnia on the other side. The focus on Lucy was simply because I recognised myself in her: the diligent, earnest sibling, easily hurt by less considerate brothers and sisters. The one who was so ready to believe in magic. If Lucy was real, I was convinced we’d be best friends.

I excelled at catching feelings for fictional characters in my tweens and teens—and even took it one step further and fell for real people I didn’t know. Nick Carter and Legolas were my first loves. In my early twenties I once constructed a detailed back story for a guy I used to walk past each morning on the way to work. We never spoke or even made eye contact. I once wrote Robert Pattinson fan mail, like actual physical mail I put in a post box. It will come as no surprise that my strongest parasocial attachments have come about during periods of intense loneliness.

Even in my current era—within a happy and stable family unit—I’m still susceptible to the pull of a parasocial current, though it’s more a source of entertainment these days than an emotional need.

Social media has normalised parasocial attachment for people like me (introverted, anxious, prone to fixations). We’re surrounded by a kaleidoscope of ‘true’ stories all day every day. We can interact with a double tap at no personal risk. We can even broadcast our own stories on social platforms (or blogs 🥲) and consider a ‘like’ or ‘comment’ to be sufficient feedback to feel validated, accepted, even loved. The need to be seen and heard is human, but the tools we now have to act upon that need aren’t designed with human wellbeing in mind.

The reality is that unidirectional relationships in the digital age do provide the illusion of reciprocity. The dopamine hit of engagement can fool us into thinking our psychological and emotional needs are being met. Perhaps most importantly, social interaction on the internet has much lower stakes than showing up with vulnerability in real life.

The act of knowing and, in turn, being known by another human being? That’s the work of a lifetime, and despite what romcoms would have us believe, it’s not pretty. Reciprocal relationships require resilience, adaptability, openheartedness, a willingness to admit fault, a readiness to compromise. Saying ‘I love you’ is just the beginning of the story. I fear the ‘social’ part of modern media is eroding our will to do the work required to build real human relationships.

When we use the word ‘parasocial’, it’s generally with reference to one-way attachment to celebrities, but it goes both ways. There just isn’t a huge amount of discourse about the one-to-many attachment that celebrities develop for the people that support them.

Lorde is on tour at the moment. Her 2025 album is one of my favourites of the year and I’ve loved watching it play out on socials every night. She’s always come across as an articulate, considered and deeply feeling person, and in her ‘Virgin’ era it’s clear her principal success metric is her own authenticity. There are no fancy costumes or elaborate stage set-ups on the Ultrasound Tour, instead she wears jeans and a simple t-shirt each night. At various points in the show she strips off layers—but not really in a sexual way—it’s like a clear-eyed movie-length exposure of body and mind. She runs on a treadmill in her underwear during Supercut and finishes the show by walking through the crowd in a glowing jacket while singing David.

Lorde shares personal insights about life on tour through her social media channels. Pool snaps that say ‘day off by the highway’ or ‘life these days is sleeping till noon and leaving it all out on the field. I’m so lucky to be your freak’.

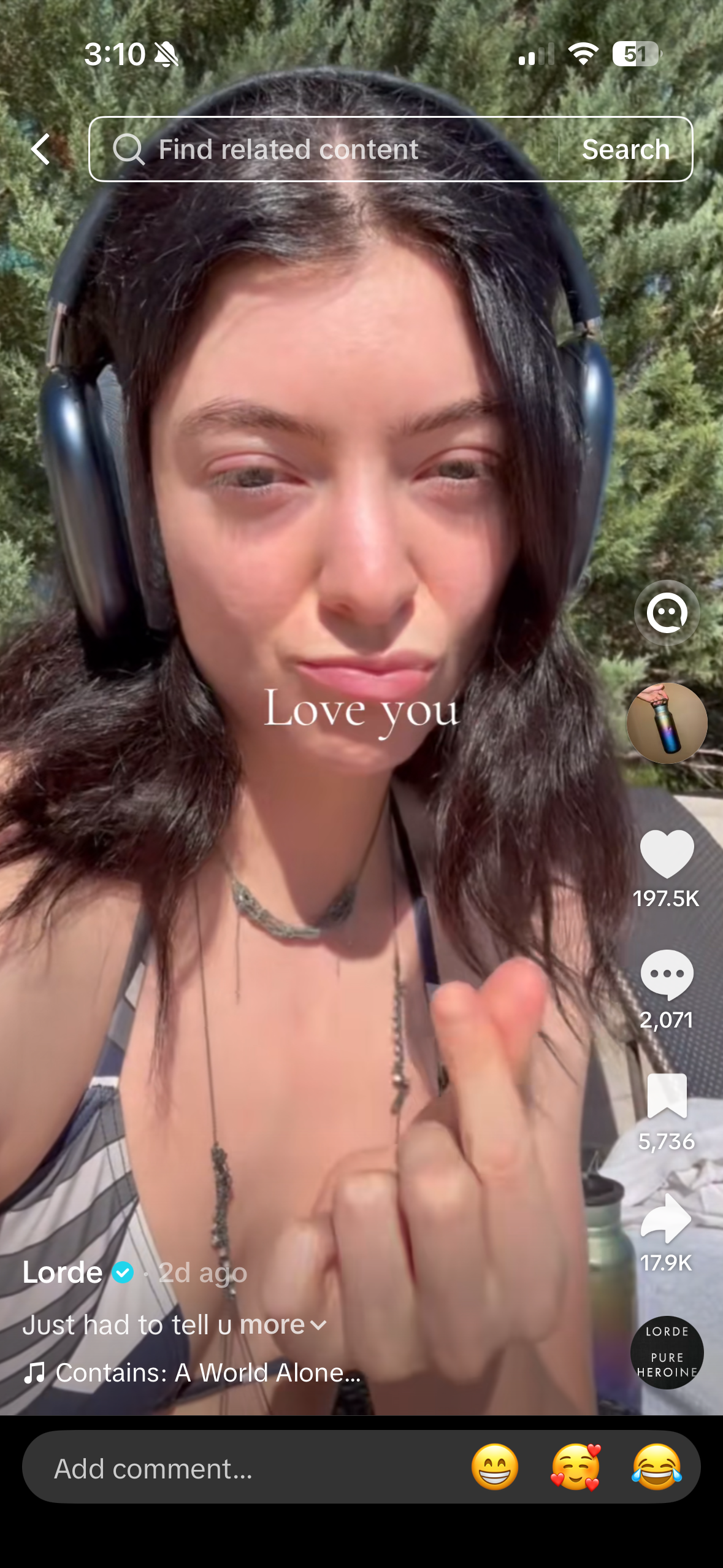

It offers such a compelling view of the headiness of it all. You can see how easily one might become addicted to the rush of feedback. A few days ago she posted a video on TikTok that simply said ‘love u (just had to tell you)’. I wondered at the impossibility of feeling ‘love’ for 800,000 people at once. She is more realistically expressing love for the feeling of being loved by them, but these kinds of expressions of love and gratitude fuel the parasocial relationship and keep the wheels spinning. I’m not trying to sound cynical. The feelings on all sides are real, but the implications of them are complicated.

In some cases, parasocial feelings can be positive. Imagined relationships are a safe rehearsal space for the real thing—a thought experiment for the socially anxious. Being part of a fandom can offer a sense of belonging and a safe space to explore identity. Perhaps most importantly, any attempt to understand another human being (or be understood by one) strengthens empathy. Researchers in psychology and anthropology have long posited that human storytelling is a cultural evolution designed to strengthen social cohesion. With that lens, our human desire to see and be seen is actually a species survival tactic.

“I wish it wasn’t this way, but I ache to be understood…A big part of why I make work is to feel the peace of being understood. … I tried to explain it less this time, but I still feel like I explained it more than I should have.” Lorde, in a recent interview with the LA Times.

Maybe one of the reasons I’m so fascinated by mass appeal/popular culture is because increasing human empathy at a mass scale has the potential to counterbalance one of our greatest failings: our blindness to selective empathy. The fact that we’re more likely to care about or help people if we recognise and understand them. When we see a child suffering through a television screen, for example, we don’t all feel the same level of anguish we would if it were a child we knew. However if we’re told that child’s story, that’s when we’re able to open the doors to empathy. If we could overcome our inability to feel the same about strangers as we do about our loved ones, how many issues would disappear?

Research shows that stepping into the mind of a character improves your ‘theory of mind’—which is your ability to read and understand the feelings of others—a key skill in maintaining social relationships. My own experience of diving into the world of BTS has expanded my appreciation for Korean culture; a new parasocial attachment that gives me a feeling of warmth and curiosity towards an entire country. How wildly powerful.

"Fiction is not just a slice of life — it’s a slice of the mind. A simulation that runs on the software of our brains, teaching us how to navigate the social world." Keith Oatley, Professor Emeritus of Cognitive Psychology, University of Toronto.

One of the perils of our digital world is that people have endless platforms upon which to tell ‘true’ stories. The line between fiction and reality is deeply blurred. It’s a double-edged sword providing both the opportunity to expand our empathy and the comfortable, isolating cushion of perceived intimacy which is but an echo of the real thing.

So the challenge for contemporary storytellers is to consider how to use tech to build narratives that increase collective human benefit while minimising harm. Can we reach a level of awareness about the mediums we use to tell stories in a considered way? Is it already too late?